Early Warning of COVID-19 Possible by Testing Wastewater

Researchers are working on a new test to detect the coronavirus that causes COVI-19 in the wastewater of communities infected with the virus.

Researchers at Cranfield University are working on a new test to detect SARS-CoV-2 in the wastewater of communities infected with the virus.

The wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) approach could provide an effective and rapid way to predict the potential spread of novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) by picking up on biomarkers in feces and urine from disease carriers that enter the sewer system.

Rapid testing kits using paper-based devices could be used on-site at wastewater treatment plants to trace sources and determine whether there are potential COVID-19 carriers in local areas.

Dr. Zhugen Yang, Lecturer in Sensor Technology at Cranfield Water Science Institute, said: “In the case of asymptomatic infections in the community or when people are not sure whether they are infected or not, real-time community sewage detection through paper analytical devices could determine whether there are COVID-19 carriers in an area to enable rapid screening, quarantine, and prevention.

“If COVID-19 can be monitored in a community at an early stage through WBE, effective intervention can be taken as early as possible to restrict the movements of that local population, working to minimize the pathogen spread and threat to public health.”

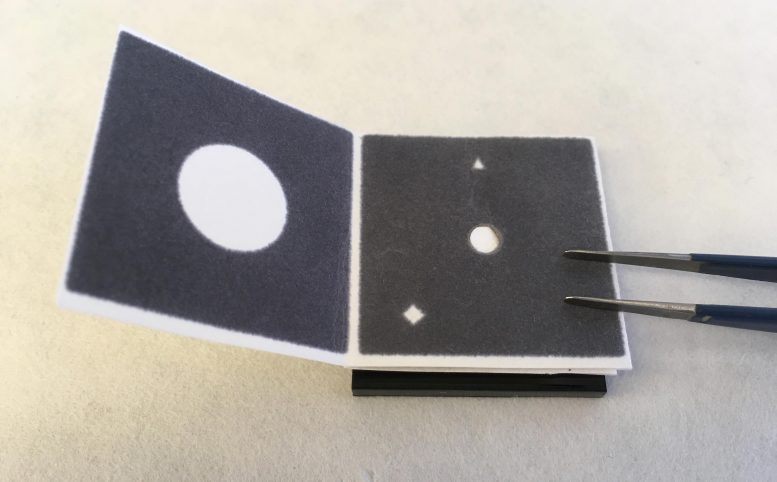

The paper device is folded and unfolded in steps to filter the nucleic acids of pathogens from wastewater samples, then a biochemical reaction with preloaded reagents detects whether the nucleic acid of SARS-CoV-2 infection is present. Results are visible to the naked eye: a green circle indicating positive and a blue circle negative. Credit: Cranfield University

Recent studies have shown that live SARS-CoV-2 can be isolated from the feces and urine of infected people and the virus can typically survive for up to several days in an appropriate environment after exiting the human body.

The paper device is folded and unfolded in steps to filter the nucleic acids of pathogens from wastewater samples, then a biochemical reaction with preloaded reagents detects whether the nucleic acid of SARS-CoV-2 infection is present. Results are visible to the naked eye: a green circle indicating positive and a blue circle negative.

“We have already developed a paper device for testing genetic material in wastewater for proof-of-concept, and this provides clear potential to test for infection with adaption,” added Dr Yang. “This device is cheap (costing less than £1) and will be easy to use for non-experts after further improvement.

“We foresee that the device will be able to offer a complete and immediate picture of population health once this sensor can be deployed in the near future.”

WBE is already recognized as an effective way to trace illicit drugs and obtain information on health, disease, and pathogens. Dr. Yang has developed a similar paper-based device to successfully conduct tests for rapid veterinary diagnosis in India and for malaria in blood among rural populations in Uganda.

Paper analytical devices are easy to stack, store and transport because they are thin and lightweight, and can also be incinerated after use, reducing the risk of further contamination.

An overview of the approach – Can a Paper-Based Device Trace COVID-19 Sources with Wastewater-Based Epidemiology? – co-authored with Hua Zhang and Kang Mao of the Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guiyang, China, has recently been published in the Environmental Science & Technology journal.

Further development of the test is being sponsored by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and Royal Academy of Engineering.

Reference: “Can a Paper-Based Device Trace COVID-19 Sources with Wastewater-Based Epidemiology?” by Kang Mao, Hua Zhang and Zhugen Yang, 23 march 2020, Environmental Science & Technology journal.

DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01174

DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01174